Vietnam is recognized as one of the world's most biodiverse…

Tien Hai Nature Reserve latest battleground in Vietnam’s push for development

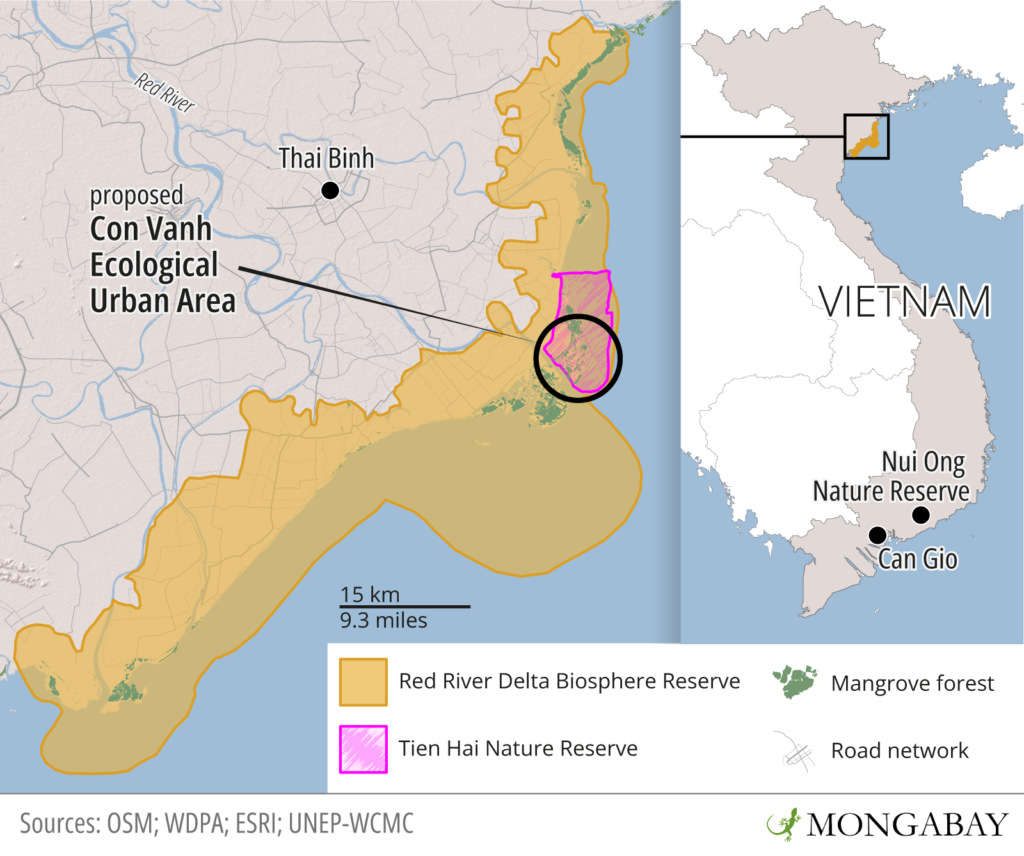

In mid-April, the government of Thai Binh province on Vietnam’s north-central coast quietly issued a decision that has since spawned growing controversy.

The decision removed protection from almost 90% of Tien Hai Nature Reserve, reducing its area from 12,500 to 1,230 hectares (nearly 31,000 to just over 3,000 acres).

According to provincial leaders, this was done to create space for the Thai Binh Economic Zone, a sprawling area currently home to several industrial parks and a coal-fired power plant, as well as a proposed residential, resort and golf course complex called the Con Vanh Ecological Urban Area.

No construction work has followed the decision, and the issue went largely unnoticed until August, when Trinh Le Nguyen, executive director of the environmental NGO People and Nature Reconciliation (PanNature), began writing about it on Facebook.

In a post dated Aug. 11, Nguyen noted that Tien Hai is part of the broader Red River Delta Biosphere Reserve. Established in 2004, the biosphere reserve spans 137,261 hectares (339,179 acres), including a core area, buffer zone and transition zone across terrestrial and marine areas.

“The core area, the heart of the biosphere reserve, includes Tien Hai Nature Reserve and Xuan Thuy National Park,” Nguyen wrote.

When created in 2014, the Tien Hai reserve included 1,430 hectares (3,534 acres) of forested land and 11,050 hectares (27,305 acres) of wetlands and mudflats, the latter of which includes swaths of rehabilitated coastal mangrove forests.

“With the reduction of Tien Hai’s area to 1,320 hectares, the Thai Binh Provincial People’s Committee may have put an end to the Red River Biosphere Reserve,” Nguyen wrote.

He added that if the reserve loses a majority of its core area, UNESCO, the U.N. agency that designates which areas qualify as biosphere reserves, can consider withdrawing the title; this reserve is subject to an assessment by Sept. 30, 2024.

According to UNESCO’s website, “Mangroves and intertidal habitats of the Red River Delta form wetlands of high biodiversity, especially in the Xuan Thuy and Tien Hai districts. These wetlands are of global importance as migratory sites for several bird species.”

A representative of UNESCO’s Vietnam office didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

Nguyen said this plan went against conservation efforts initiated by the Vietnamese government.

“The government and donors have invested a lot of money in this biosphere reserve through mangrove restoration and development programs,” he wrote. “Reducing this forest in Thai Binh clearly goes against the province’s jurisdiction.”

Nguyen’s advocacy quickly generated coverage in Vietnam’s state media outlets. Thai Binh officials defended the decision, saying it aligns with a 2019 decision signed by then-prime minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc on the development of the Thai Binh Economic Zone.

Indeed, in May 2022, the current prime minister, Pham Minh Chinh, visited Thai Binh to check on the progress of this economic zone and said local leaders should develop coastal areas to avoid problems with land clearance, a major issue when it comes to using land people already live on.

This sort of thinking is exactly what Pamela McElwee, associate professor of human ecology at Rutgers University in the U.S. and author of Forests Are Gold: Trees, People, and Environmental Rule in Vietnam, has warned about.

“Any time there is a local plan to convert a natural area into a developed area, the logic is simple: it’s cheaper than trying to plan a golf course in an area that you might have to buy back lots of individual local land plots or use eminent domain to put together a large enough land area,” McElwee said in an email. “Hence local areas look greedily at converting parks or protected areas as a quick and cheap solution to their land needs for large-scale development planning.”

McElwee, who has done field research in Tien Hai, said officials want such issues to boil down to “jobs and development vs. trees,” since they think such framing works in their favor.

“But this is wrong for two reasons: one, many local development plans are not going to bring large numbers of high-paying jobs, and local people know this,” she said.

Second, she said, the loss of natural ecosystems endangers the very development plans proposed to replace them.

“Removing protective mangroves and mudflats will get rid of natural buffers against sea level rise and storms that are increasing under climate change, threatening the development the province says it wants,” McElwee said. “Planning that incorporates ecosystem protection into some sort of integrated planning could get you both ecosystem protection combined with development, but that kind of integration is very rare in Vietnam.”

The website of Hansen Partnership, an Australian planning and design firm, lists the Thai Binh Economic Zone Masterplan as one of its projects, and says it “will require a sensitive balance between economic development initiatives, port development, investment and job creation, with the protection and rehabilitation of mangrove forests, sensitive land reclamation and working with local communities.”

Hansen’s Vietnam office didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The development tension

Two in-progress plans elsewhere in the country highlight how frequently development can come into conflict with ecosystem protection, and the often-skewed balance between the two.

Earlier this month, Vietnamese media brought attention to a plan in Binh Thuan province, on the south-central coast, to clear more than 600 hectares (nearly 1,500 acres) of forest to construct the Ka Pet dam and reservoir, aimed at improving water supply in one of Vietnam’s most drought-prone regions.

Nearly a quarter of this area includes special-use forests in Nui Ong Nature Reserve, a category that denotes forest “mainly used for nature preservation.”

In an uncommon move, domestic media outlets highlighted how well-preserved this forest is, noting that members of an ethnic minority group living in the area take great pride in the biodiversity and ancient trees.

PanNature’s Nguyen addressed this controversy in a Sept. 7 Facebook post, saying the Ka Pet project stands on firm legal ground.

“The project has been approved by the National Assembly as an investment policy,” he wrote. “In principle, this means it has followed the correct procedures for converting land use purposes according to the law.”

A mechanism exists through which the national government can review a previously approved plan for forest management, but this process hasn’t been used and would be a surprising move.

Additionally, officials in Ho Chi Minh City, the country’s economic center, want to eliminate 90 hectares (222 acres) of coastal mangrove forests to build a proposed $5.5 billion port, a project city leaders say will create up to 8,000 jobs.

The project is envisioned for Can Gio, a district of the city that includes another UNESCO biosphere reserve thanks to its extensively rehabilitated mangrove forest.

Thai Binh’s next steps

When it comes to Tien Hai, the backlash has forced provincial officials to pause, at least temporarily.

“Thai Binh said that they will review the actual area of the nature reserve but stick to the idea of giving more preference to the golf course and resort project,” Nguyen told Mongabay in an email. “They actually had to cancel the ground-breaking ceremony in August in order to respond to the public disagreement.”

Nonetheless, the resort project appears likely to win out. Vietnamese media reported that the provincial government had “clarified” its position in response to the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment and UNESCO Vietnam, both of which had requested an explanation.

The provincial administration reportedly said the term “nature reserve” as used in the name Tien Hai Nature Reserve is just a label, rather than a legal distinction, and that the reserve’s size is “primarily qualitative and lack[s] specific measurement-based research” to form a forest development strategy.

The Thai Binh People’s Committee didn’t respond to a list of questions sent by Mongabay.

“Right now in Thai Binh officials are trying to confuse everyone about what counts as a wetland, saying that the previous designation as a wetland reserve wasn’t done correctly or that they are just trying to clarify some land ownership categories, but they just got caught doing land conversion that is top-down and in violation of national regulations on forest conversion,” McElwee said.

While the future of Tien Hai hangs in the balance, conservationists are adamant that the development plans discussed above shouldn’t move forward.

“Given the fact that Tien Hai is part of a UNESCO-designated biosphere reserve, there are some international obligations that they are putting at risk,” McElwee said. “Vietnam also signed on to the 2022 Kunming Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework where countries pledged to try to achieve 30% protection of their lands and waters by 2030. Vietnam is already below the global average for protected areas by a lot, and losing some of the nature reserves the country already has is going in the wrong direction.”

Trang Nguyen, founder and executive director of the Vietnamese NGO WildAct, highlighted Tien Hai’s importance to bird populations in particular.

“Migratory birds are under immense pressure from habitat loss, climate change and poaching, and last year our prime minister asked for urgent measures to protect wild and migratory birds in Vietnam,” she said. “If Thai Binh decides to carry on with their plan, it will be a huge setback to bird conservation not only in Vietnam but globally.”

Nguyen of PanNature, for his part, had a grim assessment of the situation: “The general trend of protected areas in Vietnam is that after each review, they shrink.”

Banner image: A black-headed ibis, one of the near-threatened birds that can be found in Tien Hai Nature Reserve. Image by Thangaraj Kumaravel via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Source: Mongabay